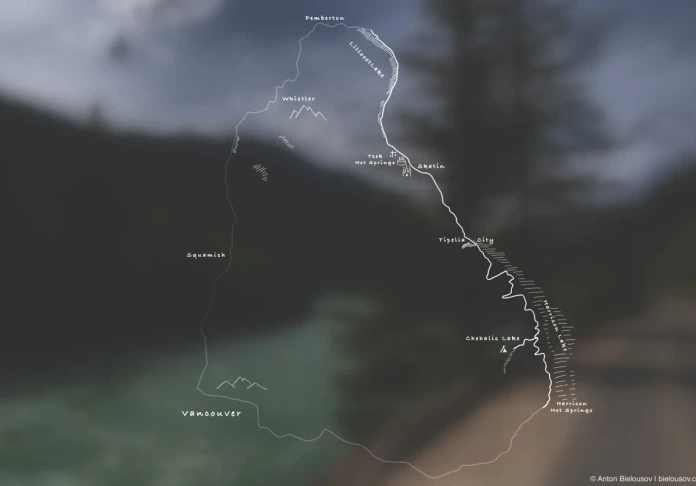

The Five Nations of the Lillooet River Route

Impressed by the northern lights the previous night, the very next evening I was hoping to catch another one, this time outside the city, while also finally reaching the end of the road along the western shore of Harrison Lake – all the way to Pemberton, and finally putting together a complete report on this remarkable route. It’s remarkable because you never know what you’ll see — fossils, a city that doesn’t exist, an abandoned church, several old Indigenous cemeteries. And of course, mountains, lakes, waterfalls, all of that. So let’s deflate the tires and hit the road!

We have 160 km of service roads ahead of us, for which Google Maps allocates 4 hours (8 hours for the entire route including the highway return). But don’t believe it — after heavy rains a few years ago, when an artificially drained lake briefly returned, the road was completely closed for a long time due to washed-away bridges. And right now, it’s not in the best condition.

This time, it took me more than 8 hours on a single service road. Although, since I traveled with an overnight stay and made many stops, not hurrying at all, maybe that’s not the best metric. But ultimately, you're here to enjoy the journey, not just to rattle along a dusty road. The first 30 km from Harrison to Chehalis Lake are very familiar to me since it’s my go-to camping spot. Heading there spontaneously, with 15 minutes to pack, at any time of year — it’s most likely going to be Chehalis.

Incidentally, this might be one of the best places to see remnants of old logging and forest fires. Oh, and logging is still active, so on weekdays, be mindful of heavy logging truck traffic.

Between the 23 and 30 km markers, the slopes along the road are scattered with fossils. Right before the 27 km marker, you can find them right by the roadside, on this slope:

Last year, I even found fossilized shells in boulders on the descent to Hale Creek, near a beach aptly named Fossils Beach. I also snapped a half-shaft there, but thanks to Toyota, I still made it home.

Mainly, you’ll find traces of fossilized shells — bivalves and ammonites. But they say cylindrical cephalopods (belemnites) — relatives of squids — can also be found, and in rare cases, even the bones of marine reptiles like plesiosaurs, mosasaurs, and similar creatures. Fossils found at Harrison Lake date back to the Middle Jurassic period (164.7 — 161.2 million years ago), precisely when a shallow sea covered what is now British Columbia – known as the Bridge River Ocean, named after the Bridge River, which flows just a few kilometers from the end of our route. With the rise of the lithospheric plate and the formation of the Rocky Mountains to the east, around 120 million years ago, the sea became cut off from the world’s oceans and eventually disappeared. That’s why we find so many marine fossils — from Vancouver Island all the way to Jasper and Banff National Parks.

In British Columbia, you’re allowed to keep fossils, but they remain the property of the province, meaning they cannot be sold or taken out of the country without special permission.

Just beyond the fossil-covered slope is the turnoff to Chehalis Lake, where we will stay overnight, hoping to catch the northern lights.

For all the times I’ve been to this lake, I only recently learned that on December 4, 2007, a landslide occurred at its far end — 3 million m3 of rock collapsed into the water from a height of 550 meters, raising a wave 37 meters high. This beach was hit by a 7-meter tsunami, and only because it happened in winter did it avoid casualties.

They say a similar landslide threat exists for the larger Harrison Lake. But if you don’t think about how at any moment a tsunami might come from over there, Chehalis is peaceful and serene, which is why I love it.

On the night sky above the horizon, a faint northern lights display could be seen.

But unfortunately, there was no light show like the previous night.

What a pity — this time, I even prepared the foreground.

Another regret — sleeping in a Jeep turned out to be less comfortable than in an FJ Cruiser, despite the flat floor. Because of the protruding center console, the mattress formed a hump — I needed a special one for this particular model, but I ended up buying a single-sized one.

Kids, on the other hand, really enjoy these trips, especially if they get a chance to steer.

Alright, moving on.

The next stretch of the journey is probably the most tedious — the road is rough, making it impossible to drive fast (especially when the little one is holding onto the steering wheel). Only the occasional scenic views bring some variety.

Mount Breakenridge. In one section, there are washouts every 50 meters — no problem for a Jeep, but SUVs with low bumpers might lose theirs there, especially since not every obstacle can be approached at an angle.

Though, there seems to be a detour road.

When the road finally descends to the water, a couple of small rocky beaches appear.

And from time to time, you can refresh yourself with the moist air from an unnamed waterfall right outside the window.

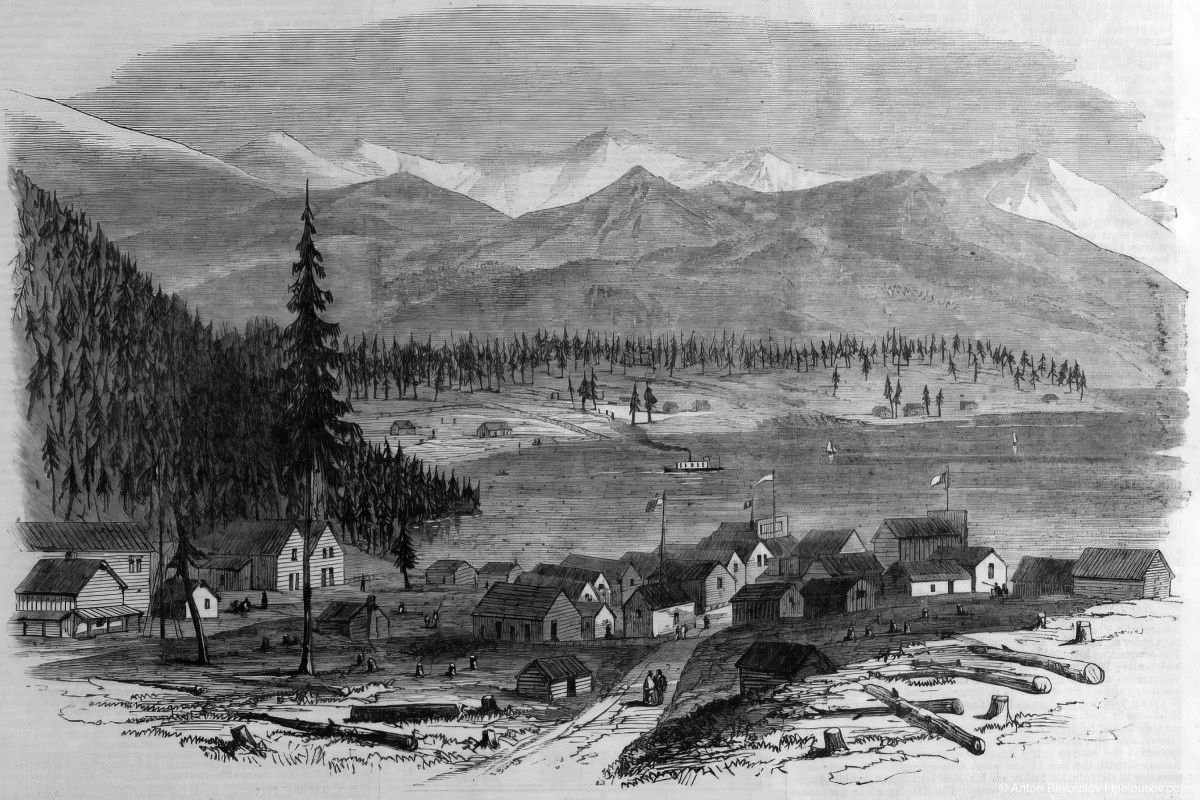

All in all, it took more than two hours to drive from Chehalis to the northern end of Harrison Lake, where the map marks the town of Tipella, which… doesn’t exist. In 1859, on the eastern shore of the Lillooet River, near the existing Xa’xtsa Indigenous settlement, the town of Port Douglas was founded. Incidentally, it was one of the first towns in British Columbia. During the height of the Fraser River gold rush, it became the second-largest town in the province (after Yale), with a population of several thousand.

The Town of Douglas And Harrison Lake, – 1864 – Sketches in British Columbia – London Illustrated News. But in 1862, gold was discovered in the Cariboo region, and the main road was rerouted into the Fraser Valley, leaving the town deserted by 1865. On the same (western) bank of the river, Tipella City was founded in the early 20th century. There were plans to build residential neighborhoods, but aside from a small Indigenous community (Xa’xtsa / Douglas First Nation), who mainly gathered herbs and berries for sale or worked at canneries in Steveston and New Westminster, the real estate venture never took off.

Over time, Port Douglas turned into a logging camp, reaching its peak activity in the 1950s. In 1970, a logging company leveled the entire area with bulldozers, erasing the last remnants of the town.

Today, there’s nothing left at the sites of Port Douglas or Tipella City except for an airstrip. However, Tipella is still marked on maps. At this point, the road changes (literally, from Harrison Mills FSR to In-SHUCK-ch FSR), improving significantly, making it accessible for any vehicle.

Of course, the opposite is also true — you can fail to reach the destination in any vehicle.

Along the road, you frequently encounter small Indigenous settlements. This one, for example, consists of 30 houses and belongs to the Skatin First Nation, which has 414 members, though only 65 live here.

A well-maintained school, where 44 students from the surrounding area study.

Contact between the Skatin people (formerly known as Skookumchuck) and Europeans dates back to the 1850s when the first road to the gold fields in Lillooet was built. French Oblate missionaries (one of the largest Catholic monastic congregations) quickly established a Catholic mission here. They required Indigenous people to settle near the mission and swiftly taught them to… live in Christ, so to speak. In 1895, the missionaries began construction on a church, inspired by images of European cathedrals but using only local materials and the skills of local residents, who could hardly be considered professional carpenters or builders. Despite the fact that all the timber was local, the nearest sawmill was in Port Douglas, and some materials were even transported to Harrison Mills — the place where this journey began.

By 1906, construction was completed, and in 1908, the Church of the Holy Cross was blessed by a Catholic bishop. Since then, it has belonged not to the church but to the community that built it, making it one of the most striking examples of "wooden Gothic" architecture that has survived to this day.

The slightly open door seems to invite you inside…

The altar, skillfully embedded in a recess shaped like the French fleur-de-lis, immediately draws attention.

A carved altar without gilding, which is fairly typical for Catholicism. An empty but ready-for-service church, reminiscent of the one in Colleville-sur-Mer, Normandy.

The worn stairs lead up to a choir balcony.

The stained-glass windows appear to have been recently restored — based on what I’ve read, they were broken before, but now they’re intact.

Near the entrance, there are two confessionals.

By the way, there has never been a resident priest in Skatin. Despite having a truly remarkable church, services were held here only a few times a year.

One of the features of this church is that it was built facing the river.

Today, the sight of the wooden cathedral’s spires in the middle of the forest feels like an unexpected encounter — even when you specifically set out to visit it.

In 1981, the Church of the Holy Cross was designated a National Historic Cultural Monument, but no funds were allocated for its restoration until the 2010s. However, judging by recent years, some progress has been made in bringing the church back to order. Many generations have been baptized, married, and laid to rest in this church, and it remains open for ceremonies in nearby communities.

Behind the church lies an old Indigenous cemetery.

A distinctive feature of local cemeteries (I encountered at least three along the way) is the presence of a large cross in the center.

Many of the graves here date back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Some inscriptions contain errors. On the oldest graves, you can see the influence of the French monastic order in the form of fleur-de-lis symbols.

I couldn’t find any old variation of the word «died» spelled as «dyied.» The closest was the old Scottish spelling «deid.» However, I’d wager this is more about general literacy. Also, note that many gravestones are inlaid with marble spheres.

Three Theresas at once — a very common name among baptized Indigenous people.

It’s reassuring that no one has vandalized this cemetery as was done in Sitka, Alaska.

Most memorable was this relatively recent grave (of someone my age, incidentally), shaped like a small carved totem, with life dates listed as «Sunrise: December 27, 1983» and «Sunset: August 25, 2017.»

Just a few kilometers from the road lies another, smaller cemetery.

And again, a large cross in the center and graves surrounding it.

With marble inlays.

However, one grave here stands out — a certain Mary, who passed away on October 11, 1922, is buried outside the cemetery. Despite this, she has a large stone monument and a personal enclosure. Unfortunately, I couldn’t find any information on what made this Mary special, but if I get a response from the Pemberton Museum, where I sent an inquiry, I will definitely update.

As in absolutely all Indigenous cemeteries I have visited, there is an atmosphere of tranquility here.

And, as usual, a couple of old ravens keep watch over order. There are at least two hot springs along this road (not counting Harrison at the start and Clear Creek on the other side of the lake). One — Sloquet Hot Springs — I’ll save for another time, but the other — Tsek Hot Spring – is a sad story.

In 2007, the government purchased this land from private ownership, where it had been for 150 years, and handed it over to the Skatin people as part of the In-SHUK-ch agreement. After the COVID pandemic (which Indigenous people feared as much as retirees), they simply… neglected it. Now, in the finest traditions of reservations, the site resembles an out-of-control landfill.

But the water flows well. Charge a fee for camping — or don’t.

Even more ironic is an ancient sign at the entrance to the abandoned campsite: «In the forest and mountains, animals don’t leave trash — only people do. Please, act like animals.» So much for civilized Indigenous communities.

And the end of the route is just a little further. The road follows the Lillooet River and then the lake of the same name.

Unfortunately, there are hardly any places to stop and conveniently access the water. But there are many scenic spots where one can overheat or break down with a view.

Though, more likely the first option — Toyota vehicles don’t break down.

On the lake, only a couple of dusty access points to the water were found, but at Lizzie Bay Rec Site, I instantly felt the urge to return for an overnight stay. At the very least, it was a place where I wanted to absorb every remaining minute of the fading day.

I even decided to reinflate my tires right there, even though there were still 15 km left before hitting the road — just to spend a little more time on this beach.

The road merges onto Highway 99 right past Pemberton. From here to Vancouver is 150 km or around 2 hours along the scenic Highway 99, which can easily be stretched into a full-day trip if one stops at all the waterfalls along the way. There have long been talks about building a highway along this route — from Harrison to Pemberton. It is meant to connect Highways 7 and 99 and is unofficially called the 5 Nations Highway. It is expected to boost tourism. However, nothing I saw suggests that these five nations are eager to attract tourists to their doorstep. But I like the name — I’ll use it in the title of this post. The five nations being referenced: Samahquam, Skatin, Xa’xtsa, Lil’wat, and Sts’ailes. Together, they form a single people — In-SHUCK-ck (named after the local name for Mount Taylor, which towers over Joffre Lake and translates to «broken like a crutch»). For now, all plans are still uncertain, but the 5 Nations Road is an excellent off-road weekend route with deep history and plenty of stories. I recommend it.